Mavis Gallant’s “Rue de Lille,” first published in the New Yorker in 1980, is only a few hundred words long—hardly two pages of the magazine. One of the main characters, Juliette, dies in the first sentence. The other, the narrator, her husband can hardly be troubled to tell us how he feels about her loss—about anything, really, other than that most Parisian of obsessions, real estate. Before the end of the first paragraph, we learn that Juliette’s apartment, which the narrator moved into after leaving his first wife, was irredeemably dark, and they’d frequently talked of moving, but never did: “Parisians seldom move until they’re driven to.” Play with that verb move a bit—move it from moving or relocating to feeling, being moved—and you have a key to this story. I was about to write “the key” but with Gallant, whose short stories of Paris often read like novels, even (or especially) if they’re especially short like this one, there is never just one bright key. Hers is the literature of multiplicity, of gesture, of the unspoken, of Paris as its own implacable character. Many of her stories are (to my eye) about waiting, but also about survival, and how surviving in Paris, as Gallant did for more than 60 years, not a few of them lean, is a triumph no matter how one's life appears to those on the outside (which would include, as it happens, the narrator of “Rue de Lille”). Don’t stop at one story. Read them all. And read her interviews, too; no one is more bracingly direct on the subject of writing, of love, of Paris.

Tues Paris Reading Rec: Christmas in Paris

A very brief post-Christmas Tuesday Paris Reading rec this week, and just to point back to my post on James Baldwin's extraordinary essay, "Equal in Paris." Because it is, among other things, a reflection on a Paris Christmas, however bleak. If you're after a brighter Paris, here's Henry James's brief take from 1876. And if that's still not enough, I point you to the series of "Christmas Journal's in Adam Gopnik's Paris to the Moon (pictured). Joyeux Noël!

A Christmasy selection from Paris to the Moon, avec champagne. May your own holidays be as merry and bright.

Tuesday Paris Reading Rec: THE MISTRESS by Philippe Tapon

For today's Tuesday Paris reading rec, a book I reviewed for the New York Times more than a decade ago, but I've enjoyed seeing on my own shelves ever since. The Mistress is a much better title than The Gastroenterologist, though the latter is much more accurate. And I'm standing by the line, "''Gut-wrenching" ... has never described a scene so well as it does a Nazi's gurgling death by the most exquisitely French means." Though this isn't really a mystery novel, if you're a fan of clever twists, you'll find a memorable one here.

“Philippe Tapon’s second novel, ‘’The Mistress,’’ is full of life’s guiltier pleasures — terribly rich food, petty luxuries, illicit romance — but the book itself is the guiltiest pleasure of all, because although it is rife with raw evil, it is altogether enjoyable. Emile Bastien lives with his mistress in Nazi-occupied Paris while his wife subsists in convenient exile in southern France, where she is stranded with neither car nor money. Emile’s reputation as one of the city’s best gastroenterologists means locals and Nazis alike clamor for his services, whatever the cost. As a result, Emile endures the lean war years very comfortably, until everything — his affair, his family, his practice and the Nazi occupation — begins to unravel. Tapon adroitly uses a small cast of characters to render the duplicities and tenuous allegiances of wartime France on an uncomfortably intimate scale. Though the plot twists and slithers almost to the level of soap opera, Tapon evokes strong emotions without resorting to tanks or bombs, mining instead the tangled domesticity of his characters’ lives. Curiously, the mistress of the title comes off as vaguely underdrawn, but it may be because she’s surrounded by so much that’s overpowering. ‘’Gut-wrenching,’’ for example, has never described a scene so well as it does a Nazi’s gurgling death by the most exquisitely French means. Reading ‘’The Mistress’’ may feel like a guilty pleasure, but Tapon has nothing to be ashamed of: it’s a fine, wicked book.”

Tuesday Paris Reading Rec: THE DEATH OF NAPOLEON by Simon Leys

A subtheme of these Paris reading recs is that I fall easily and constantly for just about any New York Review of Books book. They, like me, seem to share a predilection for all things French and keeping good books -- and old books -- in print.

Simon Leys--a pseudonym for the late Belgian professor of Chinese literature in Australia (got all that?) Pierre Ryckmans--has a wonderful, short book in THE DEATH OF NAPOLEON. As I've done elsewhere on this list, I'm going to ask for a little leeway: this is not an exclusively Parisian book; indeed, it starts on the island of Saint Helena where Napoleon was famously exiled in 1815. But Napoleon--the real Napoleon--leaves the island soon enough, having been replaced in the dark of night by a body double, a loyal soldier who'd often served that duty for him before. As Napoleon sails away, no one's the wiser, least of all the crew of his escape ship, who nickname him "Napoleon" for his vague resemblance (Napoleon is balder and fatter now) to the famous emperor. It's the first of the novel's many sly jokes: Napoleon later tours the Waterloo battlefield unrecognized and enters Paris, again, unrecognized, despite being in the company of ardent loyalists (now reduced to serving as melon wholesalers). Just when he's about to reveal himself to the world, Napoleon's body double dies--that is, for all intents and purposes, Napoleon dies, and suddenly he finds himself facing an even greater challenge than reclaiming the rule of France.

If it all sounds a bit silly -- and yes, the melons are overripe, and yes, some do get thrown -- it's meant to, but the book quite magically progresses into a graceful meditation on fame, death, and memory by its end. Like many of the other books on this reading list, and like the novel I'm publishing in April, THE DEATH OF NAPOLEON is interested in the myths humans create: why we make them, what sustains them, what ends them.

Tuesday Paris Reading Rec: DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS AND LONDON, George Orwell

In my edition of DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS, the publisher offers a charmingly indignant apology (right) for the text's absent swear words (left).

"You discover, for instance, the secrecy attaching to poverty. At a sudden stroke, you have been reduced to an income of six francs a day. But of course you dare not admit it--you have got to pretend that you are living quite as usual, From the start it tangles you in a net of lies...." --George Orwell, on suddenly finding himself impoverished in Paris.

I've been teaching creative nonfiction workshops this semester at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (go Panthers), and one thing we've gone round and round on is the role and nature of truth in creative nonfiction. At what point does the adjective outweigh the noun? How much creativity is too much?

Some people call Orwell's account of spending his late 20s penniless in Paris and London fictional, but Orwell claimed it true, that the only inventions were the arrangement of some events and the combination of some characters into one. The book passes my smell test--it feels true, it seems to convey deeper truths--even as it almost fails a second test: it's so entertaining, it almost fails to convey those deeper truths.

I read this book years ago, and hesitated to pick it up again, remembering it as unremittingly bleak. But it wasn't. The Paris pages, anyway, are almost unsettlingly fun. Orwell spends almost 50 pp. giving us a colorful picture of where and how the working poor live in 1930s Paris, and then he finds his subject: that is, he finds a job as a plongeur, a dishwasher (though he winds up doing more than that--preparing vegetables and simple meals when called upon). The behind-the-scenes material of the restaurant is so vivid, it not only recalls pages of Anthony Bourdain's Kitchen Confidential but also vaults past them:

The kitchen was like nothing I had ever seen or imagined--a stifling, low-ceilinged inferno of a cellar, red-lit from the fires, and deafening with oaths and the clanging of pots and pans. I twas so hot that all the metal-work except the stoves had to be covered with cloth. In the middle were furnaces, where twelve cooks skipped to and fro, their faces dripping sweat in spite of their white caps. Round that were counters where a mob of waiters and plongeurs clamored with trays. Sculliions, naked to the waist, were stoking the fires and scouring huge copper saucepans with sand. Everyone seemed to be in a hurry and a rage.

Indeed, such scenes, in the kitchen and the carousing after, almost capsize the book: Orwell's having too much fun. But he seems to sense this, and suddenly the narrative swerves into a consideration of the "social significance of a plongeur's life." It sounds like a terrible rhetorical move; nothing's more sure to drive a reader away than a Message. But what follows isn't cant, and isn't that radical--why should people work for so little in such terrible conditions so that others (the diners) enjoy a life of relative ease?--and, sadly, isn't at all dated.

Tuesday Paris Reading Rec: MADAME DE TREYMES by Edith Wharton

My 14 year old daughter had a problem to solve in French class (of course they take French!) the other week: she was to pair up with a classmate and craft a short back-and-forth dialogue for the class. That wasn't the problem, rather, after everyone chose partners, she found she was in a group of three. What to do? My daughter thought the answer obvious: they'd write up a dialogue where two girls were interested in the same guy. And he's interested in...

I'll leave things there, but Edith Wharton (1862-1937 )wouldn't have, and across dozens of novels, stories and novellas, never did. Though known most now for her New York Gilded Age Novels, she's always interested me for her writings on, in, and around Paris. If the Age of Innocence or The House of Mirth ever intimidated you, first, get over that, and second, start with one of her novellas, like today's recommendation, Madame de Treymes. It distills all of Wharton's most famous elements--class, money, religion, straitlaced society--into a 90 pp. novella set in Paris. Meet handsome, wealthy American bachelor John Durham, whose "European visits were infrequent enough to have kept unimpaired the freshness of his eye" and so he was

always struck anew by the vast and consummately ordered spectacle of Paris: by its look of having

been boldly and deliberately planned as a background for the enjoyment of life, instead of being forced into grudging concessions to the festive instincts, or barricading itself against them in unenlightened ugliness, like his own lamentable New York.

But to-day, if the scene had never presented itself more alluringly, in that moist spring bloom between showers, when the horse-chestnuts dome themselves in unreal green against a gauzy sky, and the very dust of the pavement seems the fragrance of lilac made visible--to-day for the first time the sense of a personal stake in it all, of having to reckon individually with its effects and influences, kept Durham from an unrestrained yielding to the spell. Paris might still be--to the unimplicated it doubtless still was--the most beautiful city in the world; but whether it were the most lovable or the most detestable depended for him, in the last analysis, on the buttoning of the white glove over which Fanny de Malrive still lingered.

The unimplicated! Unexpected, and unexpectedly perfect, word choices like that abound through the headlong rush of the next 90 pp., where Durham pursues Fanny, whom he could happily be with--and she with him--if only it weren't for the fact that she is already married. So, then, a divorce? Bien-sûr, except there's one small obstacle; perhaps Fanny's sister-in-law the eponymous Madame de Treymes, might be able to help?

I won't tell you how it ends--if you know Wharton, you know how it ends--although I do differ from many readers and critics when I say that I find a strange sense of possibility lurking in the blank part of the page beneath the final paragraph. Maybe all is not lost, maybe the sunny Paris of the first page is still sunny if--oh, but now I've implicated myself. No matter.

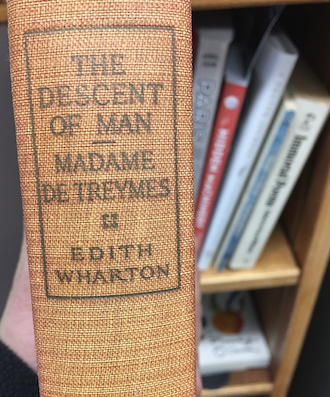

(Enjoy here if you want the raw text of the book (h/t to the Edith Wharton Society), or find yourself a pleasingly (if unfairly) dusty volume at your local library like the 1907 Scribner's edition pictured here.)

Tuesday Paris Reading Rec: PARIS WAS YESTERDAY, Janet Flanner (Gênet)

One of the theses of my novel (I know, a novel shouldn't have theses, but attendez, s'il vous plaît), is that for American kids of a certain era -- the 1970s -- The Red Balloon was fundamental to their Paris mythmaking. The not-quite-a-children's film saturated schools in those years; I remember seeing it constantly, and I had the companion book, too.

But for discerning adults in that era, and decades before, the chief Paris conjurer was Janet Flanner, who, under the pseudonym Gênet, wrote The New Yorker's "Letter from Paris" biweekly for almost 50 years, starting in 1925. The only instruction she ever had from Harold Ross (the legendary New Yorker founder, and the source of her faintly ridiculous and punny pen name) was that "he wanted to know what the French thought was going on in France, not what I thought was going on."

But what she thought invariably came through, and her acerbic, deadpan style somehow manage to give her pieces a timelines quality. The New Yorker is dangling one outside its paywall, this week--"An American in Paris"--and it's well worth a read, if only for its opening lines:

The late Miss Jean De Koven was an average American tourist in Paris but for two exceptions. She never set foot in the Opéra, and she was murdered.

But don't stop there. Indeed, it's worth getting the whole book that this piece is collected in: Paris Was Yesterday. Though she'd published anthologies of her work prior to this one, it's in this volume you can see some of her earliest work, and as a distinct bonus, read the book's introduction which ran separately in the New Yorker in 1971 and was one of the most popular pieces she ever published here. Surveying American expatriates in the 1920s, she writes, "Each of us aspired to become a famous writer as soon as possible." She then goes on to enumerate many who did--few, if any, current authors are able to refer to TS Eliot as "Tom"--and still more who did not.

As I've noted in other blog posts, the default mode for the Paris memoir is nostalgia bordering on lament. Flanner's no exception, but it's somehow sweeter here. And bleaker. And so it goes writing about Paris, I suppose. "Paris then seemed immutably French. The quasi-American atmosphere which we had tentatiely established arount Saint-Germain had not yet infrinted onto the rest of hte city. In the early twenties, when I was there, Paris was still yesterday."

(For more about Janet Flanner, consult, as I did, Barbara Wineapple's wonderfully detailed biography, Gênet.)

Tuesday Paris Reading Rec: WITHOUT RESERVATIONS

If you know Alice Steinbach, it's likely because you live or lived in Baltimore (where she was a longtime Sun columnist), or were once assigned her essay, "The Miss Dennis School of Writing," in school once upon a time. But please get to know her via her other work as well, especially her later travel books, starting with WITHOUT RESERVATIONS (2000).

Its premise is the stuff of gray Tuesday morning dreams: her sons are grown and graduated, their father by now her longtime ex-husband. Her career has gone swimmingly (including a Pulitzer), but still, she wonders: what now?

Among the many things Steinbach is entirely right about: hotel room first impressions.

This book, which charts her peripatetic, no-rush, better-part-of-a-year trip through France, England and Italy. So yes, this isn't purely a Paris book--but the Paris section is purely delightful. What's so wonderful--and so rare--about this Paris memoir is the time it takes to take in everything going on around her. It's restful, even languorous, and the ease with which friends new and old come and go from her travels (and the text) is almost enviable.

Do pick up this book. Don't give it to a close friend or family member, though, unless you're willing to risk having them hop the next Air France flight to CDG.